Author(s): Naima Imshiria*, Vahidin Katica, Lejla Imshiria, Amila Vincevic Hodzic and Nedim Galijasevic

Introduction: Bilateral ectopic pregnancy is a very rare condition which occurs in 1/725 - 1/1580 ectopic pregnancies, most commonly after induced assisted reproductive techniques.

Aim: To present the case of spontaneous bilateral tubal pregnancy, and the problem of insufficiency of available diagnostic methods, which causes that an accurate diagnosis can mostly be made intraoperatively.

Case Report: A 37-year-old female, nulliparous, comes at the Clinic of Gynecology and Obstetrics of CCUS, complains of intense suprapubic pain, and difficulty urinating. The expected menstruation was absent for more than 2 weeks. The Grav index test was positive. Beta hCG values were 6312 IU/L. On examination, the patient was extremely pale, hypotensive, gave the impression of hemorrhagic shock, and the abdomen was diffusely palpably painful. After emergency TV ultrasound, then ultrasound and CT of the abdomen and small pelvis, which indicate a moderate amount of thicker fluid in the abdomen and small pelvis in terms of hemoperitoneum and with the left contour of the uterus an oval zone most likely to correspond to ectopic pregnancy, an indication for emergency surgery was made. A laparotomy was performed, and partly liquid and partly coagulated blood was found in the abdomen. The left tube in the isthmic part was ruptured with active bleeding. Right Fallopian tube was pathologically changed, livid, with visible suspicious pregnancy in the ampullary part. Bilateral salpingectomy was performed, and samples are sent for PHD analysis that shows the presence of chorionic villi in both tubes.

Conclusion: When ectopic pregnancy is suspected, the possibility of bilateral tubal pregnancy should always be kept in mind, especially in cases accompanied by acute pelvic pain with signs of hemorrhagic shock.

Ectopic pregnancy is defined as the implantation and development of a blastocyst anywhere outside the endometrial cavity [1]. The estimated rate of ectopic pregnancies in the general population is 1% to 2% and 2% to 5% among patients undergoing medically assisted fertilization methods [2]. More than 98% of ectopic pregnancies develop in the Fallopian tube [3]. The incidence of ectopic pregnancies is increasing, which is attributed to the increase in sexually transmitted infections, the use of intrauterine devices (IUDs), the increase in the trend of surgical interventions on tubes, and the widespread use of medically assisted reproduction methods [4]. Bilateral ectopic pregnancies are very rare and occur in 1/200 000 uterine pregnancies and 1/725 - 1/1580 ectopic pregnancies [5]. In most cases, bilateral tubal pregnancy occurs after induced assisted reproductive treatment, while the rarest form of ectopic pregnancy is spontaneous bilateral tubal pregnancy [6]. There are three possible explanations for the occurrence of bilateral ectopic pregnancy: 1. simultaneous multiple ovulation 2. sequential fertilization 3. transperitoneal migration of trophoblast cells from one extrauterine pregnancy to another tube where they are implanted [7]. The mortality rate from ectopic pregnancies is high, and is the leading cause of maternal mortality in the first trimester of pregnancy, accounting for 9-13% of all deaths caused by pregnancy [8-10].

To present the case of spontaneous bilateral tubal pregnancy, as the rarest form of ectopic pregnancy, and the limitations of available diagnostic methods, in the context of faster and more reliable diagnosis of this condition, whose accurate diagnosis is still mostly made intraoperatively.

A 37-year-old female referred from the Emergency Medical Service comes to the Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics of the Clinical Center of the University of Sarajevo at night, complaining of intense suprapubic pain and difficulty urinating. The expected menstruation was absent for more than 2 weeks (about 18 days). The patient is a nulliparous, she states that she had one miscarriage in 6 weeks of gestation 3 years ago, and one failed IVF procedure as part of the treatment of primary sterility (8 years). Menstrual cycles were mostly orderly. She states that the Grav index test she did 2 days ago was positive, and that the prolactin value was >2000 ng/ml. The patient states that she has been suffering from a pituitary adenoma for the past four years, and also states thrombophilia, hyperpolactinaemia, insulin resistance. She uses in therapy: Bromocriptine tbl, Acetylsalicylic acid 100 tbl and Metformin tbl a 500 mg. She denies previous surgeries.

On examination, we find that the patient is conscious, communicative, afebrile, but extremely pale, hypotensive, and has diffuse painfully sensitive abdomen, giving the impression of hemorrhagic shock. No vaginal bleeding was observed. From the laboratory findings we single out: WBC 18.3; RBC 3:13; Hgb 106, Hct 28 and PLT 338. Beta hCG values were 6312 IU/L. Emergency TV ultrasound is performed, followed by ultrasound and CT of the abdomen and small pelvis, indicating a moderate amount of thicker fluid perihepatic, perisplenic, interintestinal, and in the small pelvis by type of hemoperitoneum and a more voluminous and heterodensing uterus. Along the left contour of the uterus, an oval zone is observed, which implies an ectopic pregnancy, so the indication for emergency surgery is set accordingly.

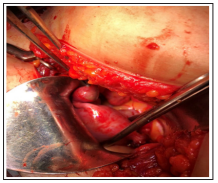

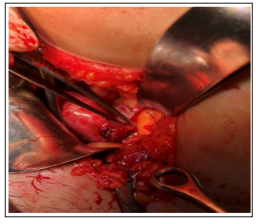

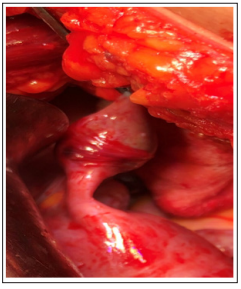

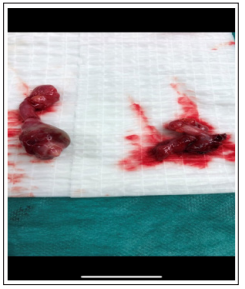

A suprapubic transverse laparotomy was performed and the following was found intraoperatively: some liquid and some coagulated blood was observed in the abdomen. (Figure 1) A ruptured ectopic pregnancy with active bleeding is observed in the isthmic part of the left Fallopian tube (Figure 2). The right Fallopian tube is pathologically changed, sausage-shaped, livid and with suspected pregnancy in the ampullary part (Figure 3). Given the intraoperative finding, it was decided to perform a bilateral salpingectomy. After the procedure, hemostasis was sufficient. The obtained materials (left ruptured Fallopian tube and right Fallopian tube with suspicious pregnancy) are sent for PHD analysis. Definitive pathohistological analysis proves the presence of chorionic villi in both delivered materials and the surface covered with cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts in the left tube (Figure 4), which indicates bilateral tubal pregnancy. Postoperative recovery is proceeding satisfactorily, and the patient is discharged home on the fourth postoperative day with normal vital parameters. The wound is without secretion, heals per primam. Advice given for correction of blood count with iron supplements. Ten days after discharge from the Clinic, the patient comes for a check-up when it is established that the patient is in a satisfactory general and local condition.

Figure 1: Intraoperative Finding After Evacuation of Hemorrhagic Content - Uterus with Associated Fallopian Tubes

Figure 2: Left Fallopian Tube Ruptured in Isthmic Part with Active Bleeding

Figure 3: Right Fallopian Tube of Pathologically Changed, Sausage-Like Appearance, Livid, with Suspected Pregnancy in the Ampullary Part

Figure 4: Material Obtained after Bilateral Salpingectomy: Left Ruptured Fallopian Tube (Right) and Right Fallopian Tube with Suspected Pregnancy (Left)

Spontaneous bilateral tubal pregnancy is extremely rare, and the most common clinical features are acute abdomen and developing hemorrhagic shock, as was the case in our example [6]. Similar to us, in the case of Ramadan et al., an abdominal and pelvic CT scan predicted the existence of a massive hemoperitoneum and left adnexal mass, indicating an ectopic pregnancy. Emergency TV ultrasound and abdominal ultrasound indicate the possibility of ectopic pregnancy in many similar cases (Ramadan et al., Allesane Tall et al., Ben Haj Hassine Amine et al., GA Al-Quraan et al.), which was also recorded in us [6, 11-13]. However, the diagnosis of bilateral tubal pregnancy in most cases is made only during the operation by examination of contralateral adnexes, which once again emphasizes the importance of a detailed intraoperative examination of the entire pelvis and bilateral examination of the adnexes (Sherman ‘s postulate - a patient diagnosed with an ectopic pregnancy is at risk of having the same condition in the future or at the same time) [14]. The type of therapeutic approach depends on the possibility of early detection of ectopic pregnancy before Fallopian tube rupture, the patient’s clinical condition, the size of the ectopic pregnancy, its location, the condition of the Fallopian tube itself and the patient’s desire to preserve fertility [6]. ACOG (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology) and RCOG (Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynecology) have issued clinical guidelines for the treatment of ectopic pregnancy without any reference to the treatment of bilateral tubal pregnancy, probably due to its infrequent occurrence.

Therefore, the general principles applicable to ectopic pregnancy also apply in the treatment of spontaneous bilateral tubal pregnancy [15, 16]. Laparoscopic surgical treatment is preferred compared to laparotomy, since the patient’s recovery is faster, and the subsequent incidence of intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies is the same [12]. In our case, due to acute condition and hemorrhagic shock, the patient was not suitable for laparoscopy or oral methotrexate treatment and required emergency laparotomy with detailed exploration of the abdomen and pelvis and evacuation of hemorrhagic contents with detection of the source of bleeding and its cessation, which is achieved by bilateral salpingectomy - the left Fallopian tube due to its rupture and active bleeding, and the right Fallopian tube due to its entire pathological change. A similar cases were reported by Ben Haj Hassine Amine et al., as well as Marwah Sheeba et al., where they have done as well as we did [12, 17].

When an ectopic pregnancy is suspected, the possibility of bilateral tubal pregnancy should always be borne in mind, especially in cases accompanied by acute pelvic pain with signs of hemorrhagic shock. The diagnosis of bilateral tubal pregnancy in most cases is still made intraoperatively, and therefore, bilateral examination of the adnexes with identification and detailed examination of both tubes during surgical treatment is mandatory. Advances in IVF and ICSI methods allow patients to achieve the desired pregnancy and offspring.