Author(s): Hamad Al-ajmi*, Abdulaziz Alfadhly, Samy Magdy, Saleh Alhasan and Mohammed Mokhtar

Internal hernia is a clinical genus that poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges and is often omitted from the differential diagnoses because of its relative rarity.

We report a case of extremely rare and atypical lesser sac intestinal herniation through a small defect in the gastro-hepatic omentum. This report details the preoperative and intraoperative diagnostic challenges and shortcomings, and also describe a novel repair technique using fibrin glue to address the culprit defect and prevent future recurrence. In this report we attempt to map out our experience against the published literature on similar cases and clinical genera and propose an anatomical and pathological model that may be used to scaffold our understanding of this clinical entity and inform relevant clinical decisions.

The omental bursa (lesser sac) is a rare site for internal herniation; this is likely due to several factors that make herniation into it difficult and mechanically disadvantageous [1]. its location in the upper abdomen places herniating structures at a vector impediment by working against gravity. The overlapping and draping effects provided by the liver, stomach, transverse colon, spleen, and the greater omentum add another layer of protection against protrusion. While the omental bursa has a single natural foramen (of Winslow), its lateral placement and draping by the liver make it inaccessible and a rare conduit of herniation [2].

The rarity of this type of hernia, the lack of pathognomic clinical features, and the paucity of published literature make timely diagnosis a challenge. The scarce reporting on Lesser Sac Hernia LSH may also explain the lack of pathological models that explain the etiological factors and the pathogenesis of such a clinical entity, which may be used to inform clinical decisions.

This case report, describes a clinical case of a lesser sac hernia, the diagnostic challenges and shortcomings, and the lessons imparted from it. We propose an anatomical and pathological model that may scaffold our understanding of this rare clinical entity. We also describe a novel treatment modality whose rationale is in emulating the natural anatomical advantageous design mechanics of the omental bursa described in the proposed model.

A 33-year-old Indian manual laborer presented through the emergency department with a two-days history of colicky abdominal pain that had a sudden onset in the epigastric region. The pain remained in the locale of its onset without radiation, shifting, or spread. It was accompanied by upper abdominal distension, nausea, and voluminous vomiting that provided temporary relief. Symptoms worsened by food ingestion; however, symptomatic dulling was reported with the use of spasmolytic and odynolytics. The patient reported worsening of his general condition over time and of becoming extremely asthenic. He volunteered no other complaints, and no other symptoms were elicited on systemic review. He denied any similar episodes in the past and claimed good health prior to this incident. His past medical and surgical histories were unremarkable, and no significant familial or environmental risks were uncovered.

The examination was positive for moderate dehydration, slight tachycardia, a temperature of 37°C, and normal oxygen saturation on room air. The abdomen was slightly distended, and palpation revealed a tender epigastrium and a tympanic percussion abdominal note, but otherwise normal abdominal and rectal examination.

Initial screening laboratory investigations revealed a mild leukocytosis of 12.6 x109, but otherwise normal renal and liver functions and normal electrolytes and pancreatic enzymes.

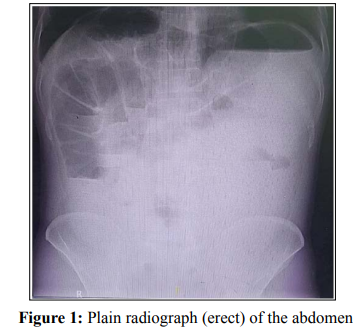

An erect plain abdominal radiograph showed a significantly elevated left hemidiaphragm by a seemingly dilated stomach with large air and fluid components. Multiple dilated bowel loopswere found in a cluster occupying the right upper abdomen with multiple air-fluid levels. The ascending and the right half of the transverse colon were dilated. There was a right infra-phrenic luminal air (Chilaiditi sign). The rest of the abdomen had a groundglass appearance. (figure 1)

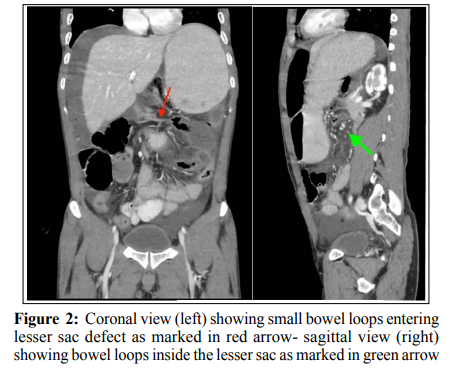

A triple contrast computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis (figure 2) showed a dilated stomach with marked narrowing of the duodeno-pyloric region. A cluster of dilated, retro-gastric small bowel loops with stretched related mesentery, mainly to the left of the midline, between the stomach and pancreas were noted. There was, however, a free flow of oral contrast down to the distal ileal loops. The mid-segment of the transverse colon showed luminal narrowing with subsequent right colonic dilation, yet there was no holdup of rectal contrast in that area. A diagnosis of an obstructive internal abdominal hernia, otherwise unspecified, was suggested, but LSH not considered.

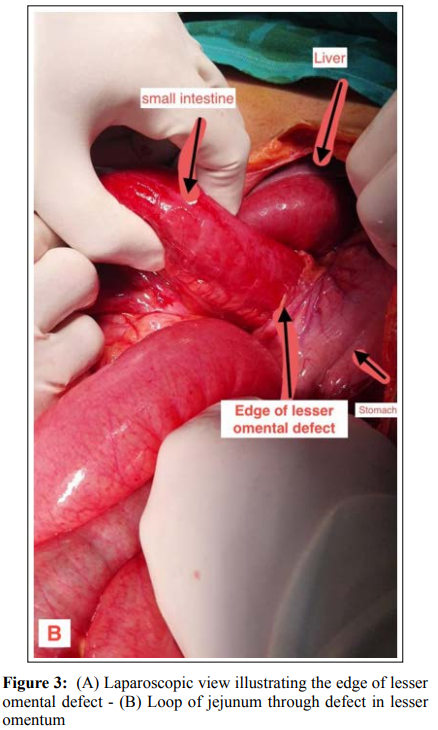

The patient was informed of the findings and consented to a diagnostic laparoscopy, which was performed via an infraumbilical 10 mm optical port and two 5mm triangulated working ports. The DJ flexure was identified, and the dilated small intestine was traced distally, where it was found to occupy the supra-colic abdominal compartment fully. At about 70 cm from the DJ flexure, the small intestine was found transgressing the gastro-hepatic ligament through a 5 cm rent in the lesser omentum. A collapsed efferent loop of the small intestine was identified exiting the defect in the lesser omentum, which was normally traced to the ileocecal junction. (figure 3a-3b)

An operative diagnosis of a Trans-hepatogastric lesser sac hernia was made. The hernial content was reduced into the greater peritoneal sac. About 200 cm of a dilated small intestine was reduced, which subsequently resulted in severely diminishing the working space. Positional manoeuvres and bowel traction failed to restore a safe working space; thus, a conversion to midline mini-laparotomy was done. Visual and tactile assessment of the herniated intestine revealed no abnormalities apart from luminal dilatation and mural edema. The transition between the dilatedand collapsed intestine was gradual, and no transitional point was identifiable.

We noted a significant hypogenesis of the transverse mesocolon at its mid-segment. This was accompanied by a rudimentary greater omentum and a sparsity of fat in the lesser omentum.

Repair of the defect was deemed necessary to prevent a recurrence, but suture repair was judged unsuitable given the insubstantial and delicate quality of the defect bearing area. Alternatively, a fibrin sealant was sprayed on the gastro-hepatic omentum, the gastric lesser curve, and the under the surface of the liver. The liver was then draped gently over the sprayed tissues until the sealant cured and a sound tissue adhesion was achieved.

The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged on the third postoperative day. He is healthy at one year postoperatively.

A lesser sac hernia is a sac-less intraperitoneal hernia. There are three types of hernias in this class; a Trans-foraminal, a Transmesenteric, and a Trans-omental type. According to the site of the causative omental defect, the latter is further divided into a greater, a lesser, and double trans-omental hernias [3,4].

Lesser sac hernias (LSH) are extremely rare, and of all their different types, hernias through the lesser omentum are the least reported. Previous abdominal surgeries, abdominal trauma, and intrabdominal inflammation have been linked as possible etiological factors [5,6]. However, LSH has been reported in patients with no apparent etiological risks; such hernias are labeled as primary LSH [7].

The omental bursa has several anatomical and mechanical antiherniation design features. Its cephalic location to herniating structures (bowel and omentum) places such structures at a vector impediment by working against gravity in most body positions. The draping effect provided by the liver, stomach, transverse colon, and the greater omentum adds another layer of protection against protrusion and intrusion into the bursa. The bursa has a single natural foramen, but its lateral placement, narrow size, and draping by the liver make it a relatively inaccessible and rare conduit for herniation. Factors that affect these anatomical design features may be responsible for the pathogenesis of omental bursa hernias.

Several anatomical findings have been linked to the development of primary LSH, which include wide epiploic foramen, hypogenic transverse mesocolon, diminutive greater omentum, and long small intestinal mesentery [8,9]. The reduced fat content of omental ligaments has been suggested as a possible factor in the developing of omental hernial defects [10].

We think that the interplay between the anti-herniation factors that we described and the reported anatomical findings linked to many reported cases of LSH may be used as an anatomically based pathological conceptual model to improve our understanding of this clinical entity, and to serve as a comparator and point of reference for future reports [11,12,13].

LSH always presents as a complicated hernia. There are no reports of incidental uncomplicated cases. The diagnosis of LSH is almost always operative. This is due to the lack of pathognomic clinical features.

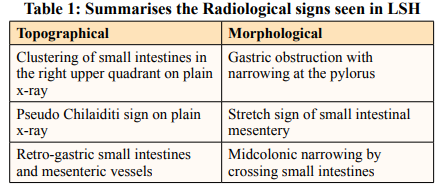

Several radiological signs have been described repeatedly in LSH case reports. These signs can be classified into topographical and morphological types (Table 1). Despite the presence of such signs, radiologists rarely make a correct preoperative diagnosis, as was the case in our report. This may be explained by the rarity of such cases and the paucity of relevant literature [8,16].

Most of the reported cases are treated by an open surgical approach Laparoscopy is feasible [14-19]. However, supra colic crowding and diminishing of safe working space may limit its utility. Making the correct laparoscopic diagnosis can limit the Incisional length of subsequent laparotomy in converted cases.

The literature on the repair techniques of such hernias is sparse. Most case reports describe suture repair of the defects, and many give no accounts of the repair to any extent [4,14,17,20]. The lesser omentum conveys the right and left gastric arteries, and their inadvertent injury by the suture passage or hernial orifice extension is possible. There are no reports on recurrent LSH in the literature, and we hypothesize that this is likely due to the formation of postoperative adhesions rather than the reliability of the herniorrhaphy. We describe a technique of repair using fibrin glue that we think is safer than suture herniorrhaphy and can be justified on the basis of enhancing the hepato-gastric draping effect and the immediate adhesions formation and obliteration of the potential site for future recurrence.

A lesser sac hernia through the lesser omentum is one of the rarest internal hernias. It has an obscure etiology and pathogenesis. Preoperative diagnosis is challenging even with the use of crosssectional radiological modalities. Laparoscopic intervention is safe and feasible; however, issues with working space may limit its utility.

In this case report, we introduce and propose an anatomical/ pathological model to inform and justify our approach to diagnostic and therapeutic decisions.

Not Applicable.

The Authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

A verbal and a written consent were taken from the patient directly prior to publishing information or images.

This work is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.