Author(s): Richmond R Gomes

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the predominant site of extra nodal lymphoma involvement. Primary gastric lymphoma (PGL) is an uncommon tumor that accounts for 4 to 20% of all nonHodgkin lymphomas and 5% of primary gastric neoplasias. Most of these lesions are either extra nodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type or diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL).(DLBCL) presents 31% of all non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (NHL). We report a case of Extranodal Marginal Zone B cell Gastric Lymphoma. Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma Clinical presentations are nonspecific; such as abdominal pain, dyspepsia or appearance of diabetes, and diagnosis is often delayed. At present, surgery is only recommended as urgent treatment for patients that present with perforation or severe bleeding, or as palliativetreatment [1-7].

A 50 years old Muslim gentleman, not known to have diabetes, hypertension, bronchial asthma or coronary artery disease was admitted in Medicine department with the complaints of recurrent upper abdominal pain for 4 months, intermittent vomiting for 2 months and heartburn, water brush for the same duration. Pain which was episodic initially, became persistent subsequently without any radiation and relation with food, dull aching in nature. He also complained of recurrent vomiting for the last two months. Vomitus contained undigested food materials but was not bile or blood stained or coffee ground in nature. He denied of having any constitutional symptoms like fever, weight loss etc. He also complained of abdominal fullness, heartburn and water brush for last 2 months. Patient was service holder, non-alcoholic; had a history of smoking about 20 pack years. He denied past history of tuberculosis or contact with tuberculosis patient. On physical examination, he was conscious, oriented with average body built. He was mildly anemic but jaundice, lymphadenopathy, clubbing, koilonychias, leuconychia and bony tenderness were absent. Skin survey appeared normal. Pulse was 86 beats/ min, regular; Blood pressure was 120/90 mmHg. Per abdominal examination revealed epigastric tenderness only. There was no abdominal mass, organomegaly or ascites. Cardiovascular and respiratory system examination revealed no abnormality.

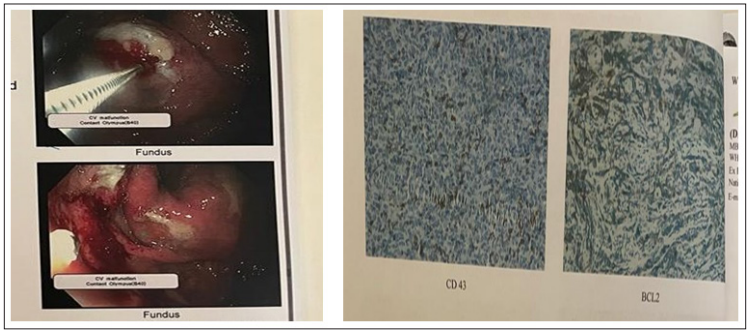

On investigation, Complete Blood Count with peripheral blood film was unremarkable, ESR was 38 mm at 1st hour, CXR PA view was normal.12 lead ECG, S. Electrolyte, S. creatinine, S. lipasewere also normal.S. bilirubin, SGPT,s. albumin, prothrombin Time were within normal range. S. LDH was mildly raised 561 U/L(normal upto 320 U/L). CT abdomen showed left sided mild pleural effusion, soft tissue density mass in the upper abdomen involving gastric wall and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Endoscopy revealed large hard mass with superficial ulceration in the fundus of stomach (Figure 1) and biopsy was taken from the affected areas and was sent for histopathology. Histopathology of the specimen revealed dense infiltration of mature looking lymphoid cells in the lamina propria. The lymphoid cells has destroyed the normal architecture in some areas compatible with lymphoproliferative disorder. Immunohistochemistry revealed BCL 2, CD20, and Ki67, CD79a positivity and CD3, CD5, CD10, CD23, CD43 negativity on neoplastic cells suggestive of extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma. (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Endoscopy of upper GIT showing large hard mass with superficial ulceration in the fundus of stomach and Figure 2: Immunohistochemistry revealed BCL 2, CD20 positivity suggestive of extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma

So we concluded that this was a case of primary gastric lymphoma (Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, B cell type) and referred to surgery department for local resection and adjuvant therapies.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a collective term for a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative malignancies with differing patterns of behavior and responses to treatment. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the predominant site of extra nodal NHLs. Several reports have shown that about 5-7% of all gastric malignancies are primary malignant lymphomas. It consists about 20% in the small bowel and 0.4% in the large gut of all the malignancies of the respective site. The most common site of extranodal lymphoma is the stomach. But compared with carcinoma incidence, NHL is rare, representing 2% to 8% of all gastric malignancies. Most of the NHLs (80-90%) are of B cell origin [8-11].

According to Dawsen et al, gastric lymphomas are defined as primary when the stomach is involved primarily and if associated intra abdominal lymphadenopathy present, it corresponds to the expected lymphatic drainage of the stomach. There will be no palpable subcutaneous nodes, mediastinal nodes and organomegaly as well as no abnormal leucocytes on peripheral blood film or bone marrow aspirate. Most patients are usually in their sixth decade. Males are more affected and it is more common in white population [12-14].

The most common site for extranodal primary non- Hodgkin lymphoma is the stomach. It presents as low-grade mucosaassociated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in 40% of the cases and as high-grade diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in 60% [1,15]. Primary gastric lymphoma frequently presents with nonspecific symptoms and diagnosis is often delayed. Nonspecific abdominal pain (50%) and dyspepsia (30%) are the most common presentations. B symptoms (fever, night sweats, and weight loss) are infrequent, in contrast to nodal lymphomas, causing diagnostic delay. Occasionally a palpable abdominal mass is found. Features of obstruction, bleeding and perforation are uncommon. Usually the features do not differ much from that of gastric carcinoma [16,17].

Imaging studies can reveal wall thickening, but in general it is difficult to distinguish gastric lymphoma from other types of gastrointestinal cancer through that medium. Regarding investigations, complete blood count with peripheral blood film, chest radiographs and bone marrow aspirates should be done to rule out metastasis Endoscopy and biopsy are more reliable methods for confirming diagnosis. The common findings are a diffuse infiltrative process, superficial ulceration or polypoidal mass protruding into the lumen [18,19]. CT scan of abdomen can figure out the extent of the lesion and metastasis; but it cannot differentiate metastatic lymphadenopathy from reactive hyperplasia [17]. Endoscopic ultrasound is fairly accurate in detecting the presence of perigastric lymphadenopathy and depth of invasion. Immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry of the biopsied material should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and for accurate sub typing. Ann Arbor staging system is not optimal to stage primary GI lymphomas, now Paris staging system is used widely for this type of malignancies [20,21].

Today, primary gastric lymphoma treatment has moved away from surgery, in favor of chemotherapy regimens. Surgery is no longer the cornerstone of treatment and is limited to cases of perforation, bleeding, and tumor-related obstruction [1,4,6].

In that context, patients with primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma related to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) that have favorable characteristics are eligible for bacterial eradication therapy as exclusive treatment, maintaining conventional chemo immunotherapy for nonresponder patients [5].

Though surgical resection remains the primary treatment, with the improvement t in antineoplastic regimens specially in the treatment of NHL’s, now-a-days multimodality therapy of neoadjuvent chemotherapy and stomach preservation has become more popular. Treatment varies according to the histology of the malignant lymphoma. CHOP regimen alone (Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) or with addition of some newer drugs like rituximab (R-CHOP) have shown promising result in the treatment of primary gastric lymphoma. Chemotherapy is also preferred in widespread disease. Radiotherapy is the choice when the tumor is incompletely excised [22-24].

The cause of perforation in gastric lymphoma is different in cases that receive chemotherapy and those that do not. Perforation in patients that receive chemotherapy is due to the weakening of the gastric tissue, associated with rapid tumor necrosis and tumor lysis due to chemotherapy. On the other hand, there are 2 different patterns of spontaneous perforation. First, spontaneous perforation results from an ulcer and tumor necrosis that has reached the subserosa. Second, perforation is the result of an ulcer that has thin conjunctive tissue and the absence of tumor [25].

The histologic subtype and grade of lymphoma can have a significant impact on prognosis. Five year survival rate for low grade stage IE & IIE disease ranges from 80-90%; whereas high grade of such lymphomas ranges 39-74%. The spread of the disease to serous layer of the stomach and intra abdominal lymph nodes also indicate poor prognosis [26].

In short, the best treatment should be chosen according to tumor location, clinical stage, pathologic pattern, and the presence or absence of complications. Overall 5-year survival reported for multimodal therapy is between 50 and 70% [1,16].

Primary gastric lymphoma is a commonest gastrointestinal tract lymphoma usually affecting elderly males. It usually presents at advanced stage. The frequency of clinical presentation of gastric lymphoma complicated by obstruction and perforation is extremely low .Treatment mainly comprises chemotherapy and surgery, if indicated. Here we present a case of primary gastric lymphoma with intent to make physicians aware of this common lymphoma which is aggressive and fatal if left untreated.

Conflict of interest:None declared