Author(s): Hatim Abid*, Mohammed El Idrissi, Abdelhalim El Ibrahimi, Abdelmajid Elmrini, Nissrine Amraoui, Meriem Meziane and Fatima Zahra Mernissi

Erysipelas is the most common bacterial dermal-hypodermal acute not necrotizing infection [1,2]. Its evolution is usually mild but can be complicated mainly by local abscess or necrosis [3-7]. In this context osteo-articular complications and septic acute tenosynovitis are rarely described in the literature with a rate of 1.2% [3]. We report in the light of a literature review a case of recurrent erysipelas of the leg in a young patient of 29 years complicated by septic acute tenosynovitis of the flexor hallucis longus (FHL), to remind this complication mainly observed in severe forms of erysipelas which is not the case of our patient.

The lower limb is the most common location for erysipelas [3]. In its classic form, the disease appears as a bright-red, spreading, superficial, edematous lesion with sharply demarcated edges [7]. Its evolution is usually favorable to antibacterial therapy in primary care. However, local complications remain possible particularly in the presence of risk factors as obesity, diabetes mellitus, age greater than 50 years, female gender, smoking, cardiovascular history, lymphedema and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs taking [8].

We share through this article in the light of a literature review, the case of a septic acute tenosynovitis of the FHL which is rarely described in healthy patients as a locally complication of erysipelas [9].

We report the case of a young sportive male of 29 years, with an antecedent of erysipelas of the right leg 10 years ago following which he kept a slight lymphedema. The patient presented abruptly a second episode of erysipelas (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Clinical presentation of erysipelas of the right leg and foot

The general examination revealed a feverish patient in 39°. Skin examination found painful erythematous edematous and hot right leg extending to the right foot without gravity signs, associated with slight lymphedema and an intertoe intertrigo. At this stage, the rest of the physical examination was normal.

Laboratory test showed hyperleukocytosis with neutrophils predominance at 18800 cells/mm3, an increased C-reactive protein (CRP) at 322 mg/L, a procalcitonin (PCT) at 0.66 ng/ml, a negative hemocultures with a normal value of glycemia. Plain radiographs of the foot and ankle showed no abnormality.

The patient was put under penicillin G. An initial clinical and laboratory improvement was noted, hence the switch to the oral pathway after the sixth day of treatment. The evolution was marked a day later by the onset of inflammatory tumefaction of the medial malleolar associated with palpation pain of the FHL tendon throughout its course from the posteromedial ankle region to the base of the last phalanx of the great toe particularly when the ankle and hallux are maximally dorsiflexed.

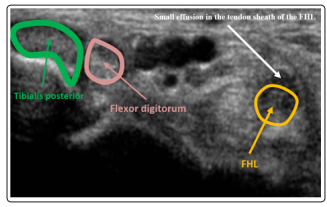

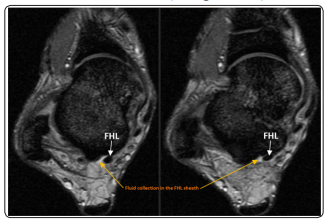

The joint ultrasound and MRI revealed a small effusion of the tendon sheath of the FHL evoking in the context a septic tenosynovitis of the FHL (Figure 2 and 3). Therefore, the patient was put first under injectable antibiotics based on quinolones and gentamicin and operated by limited catheter irrigation technique. The Antibiotics were continued orally until CRP negativation obtained around 6 weeks. To prevent erysipelas recurrence, the patient was put under Benzylpenicilline Benzathine (2.4 MU/3week). Stockings and rehabilitation were prescribed for the management of the lymphedema

Figure 2: Joint ultrasound revealing a small effusion (white arrow) of the tendon sheath of the FHL (orange arrow).

Figure 3: T2-weighted MRI of the ankle demonstrating high signal fluid (orange arrow) surrounding the low-signal of the FHL (white arrow)

Local and systemic complications are possible during erysipelas. They are the cause of prolonged hospitalization, death and are mainly observed in severe infection forms which is not the case of our patient who presented an associated slight lymphedema as a recurrence risk factor [10].

Local complications are seen in 5% to 10% of cases, they occur in the context of disease evolution in the absence of treatment or appear after incomplete improvement under treatment as seen in our patient [10]. Next to abscess, necrosis or deep phlebitis, osteo-articular complications such us osteomyelitis, synovitis and bursitis are rarer and whose rate is estimated at 1,2% [3,4,11]. In the same frame, septic acute tenosynovitis is even less reported in the literature.

Septic acute FHL tenosynovitis manifests clinically by pain that traces the path of the tendon sheath ranging from the posterior leg to the plantar foot and the hallux and can be awakened by local pressure and tensioning of the tendon. Often it is associated with edema, fever and chills [12]. Untreated septic acute tenosynovitis exposes to infection dissemination to adjacent tendons, joints and subcutaneous tissue, which implies a risk of cellulitis, arthritis or sepsis. Locally, the affected tendon may be the subject of a rupture. [12].

From a bacteriological point of view, the most implicated germ is the staphylococcus aureus with a percentage of 80% [13]. Then follow each other in decreasing order of frequency the β-hemolytic streptococcus in 30% of the cases, the staphylococcus epidermidis and the Gram negative bacilli with the same percentage around 20% [14]. In practice, germ detection is usually difficult. Indeed, cultures are often sterile and samples of the front door are inconclusive [15]. About that, studies have shown that in 20 to 68% of the time, no bacteria are ever isolated [16,17].

Complementary imaging studies are important to confirm the diagnosis [18,19] with the exception of standard radiography which is usually normal especially if it is prematurely realized but makes note of the arguments against a bone or joint disease of neighborhood [20].

Osteo-articular ultrasound which is an inexpensive, repeatable and non-invasive tool, represents the key to detect first a collection in the sheath tendon and in the second place to study the tendons and joints neighborhood [21]. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) permits the visualization of edema and inflammation. It specifies the anatomic extent of the infection and displays an associated abscess [22,23].

Prompt diagnosis of septic acute tenosynovitis can be challenging, but early recognition and initiation of treatment is essential to avoid complications and preserve extremities function [24]. In this context, the literature review highlights the importance and the benefits of systemic antibiotics alongside surgery in the treatment of this rarer local erysipelas complication [24].

Regardless of the pathogen, management of septic acute tenosynovitis includes prompt administration of empiric intravenous antibiotics. Prior to obtaining culture results, antibiotic selection should cover gram-positive organisms, including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species. Empiric antibiotics should also cover gram-negative rods and anaerobes especially in immunocompromised patients. Once the precise organism is isolated, the antibiotic regimen should be narrowed to target the specific bacteria identified [25,26]. Some reported the use of intravenous (IV) antibiotic postoperatively after surgical debridement [27] whereas others suggested that antibiotic therapy should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is made [28-30]. About that, Giladi et al could not differentiate in their systematic review the outcomes between these approaches [24].

Recently, there has been work trying to elucidate the role of local antibiotics and corticosteroids in the treatment of septic tenosynovitis [31]. In a cadaveric model, the authors found that bacterial load by direct colony counting decreased by 18.5% with saline irrigation alone, 42.6% with irrigation and local steroids, 54.4% with irrigation and local antibiotics and 77.3% with irrigation and both local antibiotics and steroids [31]. Thereby, adjunction of local antibiotics and corticosteroids to better eradicate the infection could be considered in the currenttreatment of septic tenosynovitis [25,31].

Concerning surgical procedure, it contains theoretically at first the excision of the front door with a systematic wash of the synovial sheath. According to the local observation, the intervention can be completed by a synovectomy and much wider excision [12]. Technically, in the literature, the opinions are divided between two main attitudes that are aggressive open surgical debridement and limited catheter irrigation technique. The results from smaller comparative technique studies [32-35] support that aggressive open surgical debridement exposed to a high risk of joint stiffness and tendon adhesions. However, limited entry into the flexor sheath utilizing catheter irrigation results in better overall range of motion outcomes without increased risk of infectious complications.

Lui T H described in the context of minimally invasive approach, the combined arthroscopic and tendoscopic procedure to manage FHL septic tenosynovitis and first metatarsophalangeal (MTP1) synovitis after prick injury [36]. According to the author, the advantages of this technique include small incisions which provides better cosmetic results, less chance of painful scar formation and thorough exploration and debridement of the FHL tendon and the MTP-1 joint [36].

The prevention of the occurrence of septic tenosynovitis passes above all by the prevention of erysipelas and the control of its risk factors. It is based first on the identification and effective treatment of the front door. In this context, Long-term prophylactic antibiotics therapy with oral or intramuscular penicillin or macrolides is aimed at eradicating and preventing the growth of bacteria [37- 41]. Several learned societies advise initiating treatment after the second erysipelas episode [42-44]. The International Society of Lymphology [45], the Infectious Diseases Society of America [46] and the French Society of Dermatology indicate that repeated, frequent or several episodes of prophylactic antibiotics therapy are necessary [47]. In addition, maintaining the integrity of the skin barrier is essential in this preventive approach. All documents call for Avoiding dry and cracked skin, treating macerated skin and fungal foot infections [48-50]. Chronic lymphedema foster the growth of bacteria and fungi and impair the body’s ability to produce an appropriate local immune response [51,52]. Different methods have been described to treat this accumulation of fluid in the tissues most of which are non-operative and act principally by mechanical compression and increasing of blood and lymphatic flow thanks to compressive bandages, elastic stockings, physical therapy and exercise. Diuretic treatment generally works through the production of urine and shifting of the body’s fluids from the swollen tissues into the blood vessels, and weight loss works by reducing limb volume and the facilitation of vascular flow and lymphatic drainage [53,54]. Surgical techniques to treat lymphedema have slowly been introduced, aiming to reconstruct a lymphatic drainage system and to remove overgrowing tissue, including the removal of fat tissue (liposuction) [54,55].

In our context, the patient was operated through a medial approach by limited catheter irrigation technique. Parenteral antibiotics were started immediately following tissue sampling addressed to bacteriological and histological analysis. Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus was isolated on culture. The IV antibiotics were continued until edema, pain and inflammatory markers improvement. The patient was then switched to an oral regime for a duration of 6 weeks. Six months after surgery, the patient had resumed sports activities and inflammatory markers remained within normal limits.

This case report underlines one of the rare but potential complication of the leg erysipelas namely septic acute tenosynovitis of the FHL tendon. Benign in appearance, this complication can have serious consequences, particularly in a young athlete by bringing into play the functional prognosis of the ankle. Consequently, an early diagnosis of this affection is essential for establishing the appropriate treatment. The prevention of septic acute tenosynovitis of the FHL tendon passes above all by the prevention of leg and foot erysipelas recurrence and the control of its risk factors.