Author(s): N Chandra Wickramasinghe, Maximiliano CL Rocca, Gensuke Tokoro4 and Robert Temple

We explore the idea that influenza pandemics may arise from the transference of new virions (new sub-types of the influenza virus) of cosmic origin in general accord with the theory of cometary panspermia. Such a transfer process will be modulated by the sunspot cycle and through its role in affecting the interplanetary magnetic field configurations in the Earth’s vicinity. Transfers of virus could take place directly from comets or indirectly from a transient repository represented for instance by the Kordylewski if dust clouds at the L4 and L5 Lagrange libration points of the Earth-Moon system. In either case an active sun appears to be a perequisite for effective transfers. The long remission of influenza pandemics throughout the period 1645-1715, during the Maunder sunspot minimum, might be understood on the basis of our model

The etymology of the word influenza immediately connects with astronomy. Derived from Latin word influentia, meaning “to flow into” it seems to have been first used from early medieval times to describe an epidemic disease that we now recognise as influenza. It was believed to be caused by an invisible fluid that emanated from the stars causing a disease that intermittently ripped through the human population. In 1743 Italians experienced an epidemic that spread across much of Europe, and called it influenza di catarro (“flow of catarrh”). Thereafter the disease came to be known in English simply as “influenza” [1]. A viral cause of the disease was securely established only after the 1930’s, but many mysteries concerning its epidemiology, and in particular the times of occurrence of pandemics, still remain unresolved [2,3]. In this paper we explore further a possible link between an aspect of the behaviour of our local star the sun–the sunspot cycle, and the emergence of pandemic influenza.

Despite nearly half a century of research on a wide range of aspects of solar physics, it is fair to say that our parent star still holds many of its secrets. The sun’s dipole magnetic field reverses polarity every 11 years, the switch happening close to the maximum of each 11-year solar cycle. During each field reversal event the sun’s polar magnetic field strength will weaken until it reaches zero and thereafter begin to recover with the opposite polarity. This field reversal appears to be closely related to sunspot activity and has an effect on interplanetary magnetic fields and in particular the fields that connect the sun and planets including the Earth. An early model to explain the process of field reversal involving an Ohmic dissipation model was proposed by Hoyle and Wickramasinghe as early as 1961, but since then no significant advances in our understanding appear to have been made [4]. On the other hand, space exploration over the past decade has unravelled the changing configuration of a magnetic bubble that surrounds the Earth (the magnetopause) as it is buffeted by a varying flux of protons, positively charged ions and electrons from the solar wind.

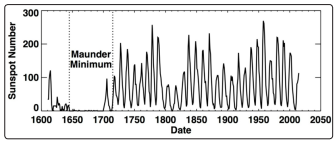

The Sunspot cycle has an average period of very close to 11 years. Individual cycles could be longer or shorter by an average of 1.5 years, and over a much longer time interval periods of remission (with very few spots or no spots) can be seen over extended intervals. Two protracted minima of the sunspot cycle are on record since sunspot data first began to be recorded – the Maunder minimum (1645-1715 CE) and the Dalton minimum (1800-1830 CE). Both these minima have been marked by a preponderance of pandemics of various kinds – Small Pox, English Sweats, Plague and Cholera [5]. In this article we discuss a possible connection between the sunspot cycle and the incidence of pandemic influenza.

A discussion in general of a possible link between solar activity and epidemics of viral disease hinges of the theory of the origin and evolution of life developed by Fred Hoyle and one of us from the late 1970’s and which is currently looking to be increasingly more plausible. This theory of cometary panspermia has comets playing a crucial role–cometary dust and debris carrying bacteria and viruses are required for both the origin and subsequent evolution of life [3].

There is now much evidence to support the view that our genetic inheritance may be comprised of DNA actually delivered through interaction with viruses [6]. In human DNA this shows up as LINEs (Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements, 21%), and SINEs (Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements, 13%) which are derived from retroviruses, HERVs (Human Endogenous Retroviruses) and LTRs (Long Terminal Repeats, 9%).

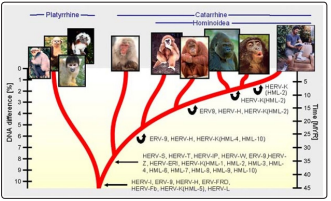

In a recent paper we discussed the possibility that the defining characteristics of Homo sapiens may have been introduced into ancestral Anthropoidea primates 35-40 million years ago when the Earth was being showered with cometary debris carrying viral genetic material [7]. Further genetic developments along our ancestral lineage appear to have been punctuated by a series of repeated viral or retroviral pandemics presumably similar to the AIDS virus. In each such pandemic the entire evolving line may have been culled save for a small surviving number carrying ERVs (Endogenous retroviruses) that have retained the potential to introduce novel traits. This feature is clearly seen at each branching point of a reconstructed evolutionary tree as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Evolution and branching of hominid lineage marked by retroviral inserts at crucial branching points

Although the long-term evolutionary role of the influenza virus is unknown, it is an instance of yet another virus that may conceivably have a long-term effect on evolution and could thus be interpreted as part of a cosmic milieu of viruses.

The principal mode of introduction of viruses of cosmic origin that could be involved in evolution has been argued to be comets–comets in our own solar system, combined with intermittent involvement of exo-comets, or comets stripped away from exoplanetary systems that could gain ingress into the inner solar system. The recent comet Oumuamua (A/2017U1) in a hyperbolic orbit may well fall into this category. In a recent paper two of the present authors discussed recent astronomical data that led to the confirmation of the existence of the hitherto disputed “Kordylewski Dust Clouds” located at the L4 and L5 Lagrange points of the Earth-Moon system ~ 400,000km from the Earth [8].

The new data yielded reliable estimates of the size of the Kordylewski Dust cloud at L5 as well as the average radii of the individual scattering/polarizing dust particles in the cloud’s interior. The diameter of the cloud was estimated to be somewhat less than 3 times the Earth’s diameter, ~ 40,000km, and the average radius of dust grains in the clouds was estimated at ~ 3 x 10- 5cm. This is consistent with bacterial-type cells, with a mean separation of less than 1 cm. There can be little doubt that these Kordylewski clouds can serve as an ideal repository for mopping up cosmic bacteria and viruses that approach the Earth-Moon system. The temperature of unshielded dust in the outer layers of the clouds would be about minus 20 degrees C, but even lower in shielded interior regions within the clouds. These conditions make it possible to cryopreserve microbiota under anaerobic conditions for considerable lengths of time.

We have not previously explored the possibility that panspermic events that might lead to pandemics might involve the transference to Earth of microbiota–bacteria and/or viruses-from these relatively nearby clouds. This process could plausibly be driven by the sunspot cycle and the effects of solar winds that could disrupt and peel off the outer layers of these clouds. During prolonged periods of a quiescent sun this particular mechanism for the introduction of bacteria or virions to the Earth is likely to be interrupted thus leading to a halting of some types of pandemics. In the next section we make a case for arguing that influenza pandemics may well fall in this category

Influenza is a viral disease in humans that occurs both seasonally and as major pandemic events. We refer here to pandemics of influenza which can be interpreted as the introduction/emergence of a new sub-type of the virus to which the entire human population has no immunity. The possible time-correlation between the viral influenza (type A) pandemics and the Sunspot cycle was explored by Hope-Simpson and Hoyle and Wickramasinghe [3-11]. A causal link between the peaks of confirmed or probable influenza pandemics and peaks of the sunspot cycle appears at first sight to be strong, although later studies by Qu discuss cases where pandemics also occur closer to the troughs of the cycle in a few instances [12]. The pandemics occuring close to the peaks of the sunspot cycle may arguably refect the influence of solar X-ray emission that also peaks near sunspot maxima and may have mutagenic effects on incoming viruses. A more likely connection could be in the electrical fields associated with auroral activity that also peaks at sunspot maxima. Charged influenza virions could have rapid entry into the polar atmosphere along electric fields [3]. On the other hand the relatively few viral pandemics found to occur near sunspot minima may reflect the relativedly free access of charged influenza virions across all geographic latitudes, unfettered by the magnetic shielding of the Earth that is weaker at such times. The distinction between minor modifications of an already circulating endemic influenza subtype on the one hand, and the introduction of new subypes or recombinant subtypes on the other confuse the issue between two competing processes that may be at work.

In our model of a cosmically driven biological evolution process, access to new viruses is dependent on the viral/microbial environment through which the Earth moves through space. A variable viral input could arise from interactions which different comets within the solar system, as well as via encounters with extrasolar comets that may add to the dust/viral content of the interplanetary medium through which the Earth moves.

The Maunder Minimum, also known as the “prolonged sunspot minimum”, is the name used to describe the period around years 1645 to 1715. During this entire period sunspots became exceedingly rare and so also the sightings of auroral events [13]. Solar activity had been inferred at earlier times in the “proxy” record of 14C and 10Be. High fluxes of neutrons arising from the decay of cosmic ray protons (which are more prevalent during sunspot minima) cause the production of 14C and 10Be which is deposited in ice cores; so the prevalence of these nuclides are used to extrapolate the solar cycle prior to 1600.

Figure 2: Data of sunspot numbers from 1600 to the present time. Data from which curve is plotted is from public access records of the Royal Observatory of Belgium

The Wolf, Spo?rer and Dalton minima which we have discussed elsewhere are all earlier minima inferred from this nuclide data, but their precision and reliability may be called to question [5]. In any event the Maunder minimum is the best documented, deepest and most prolonged minimum of sunspot activity on record for possibly ~1000 years [14]. The Maunder Minimum is also associated with a simultaneous long period of a very cold weather in the northern hemisphere known as “The Little Ice Age” [15].

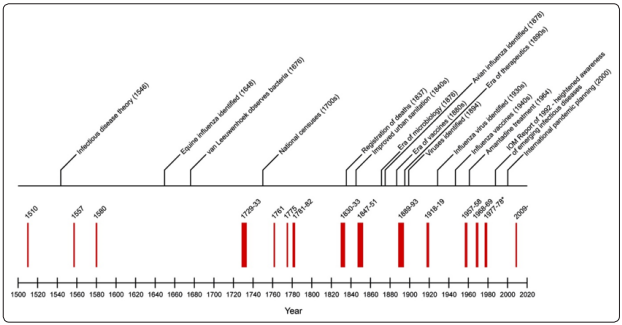

Figure 3 shows the record of influenza pandemics as well as relevant developments in medical recording and history from a combination by Pyle [16]. The last major pandemic that can be been inferred to be influenza and described as “severe and lethal” occurred in 1580 and ripped across Europa, North Africa and Minor Asia throughout that year [16]. This happened during a Sunspot maximum in the same year during which a great magnetic solar storm was reported on 6- 8 March, 1582 [17]. After this cataclysmic pandemic event there was a conspicuous absence of any pandemic that has been identified as influenza throughout the entire 17th century [16,17]. A few seasonal local epidemics of influenza have been recorded but none that was severe enough or lethal to be classified as a pandemic [10,16,19].

Moving forward from 1510 …….. From the time of the pandemic of 1580 to the next influenza pandemic in 1730 there is a lapse of 150 years. This is the longest inter-pandemic period of time recorded during the last 500 years of records of influenza epidemics and pandemics [16,18]. The next clear evidence identified as an influenza pandemic outbreak was reported in Europe in 1729-1730, again this occurred during a Solar maximum [18].

It is worth noting that during the same period (second half of the 17th Century) there were major pandemics of bubonic plague (e.g., London, 1665-1666) and typhus, all caused by non-viral pathogens [5]. Our provisional inference is that whilst pandemic influenza virus was excluded from arising or entering the Earth during the prolonged sunspot minimum in question the arrival of non-viral (bacterial) pathogens may have been somehow facilitated, perhaps resulting from the weakend magnetosheath that surrounds the Earth [15]. Finally, we note that after the year 1730 there is an uninterrupted sequence of influenza pandemics on record including the 1918/1919 pandemic. All these pandemics occurred either during or very close to sunspot maxima, and these times were also accompanied by significant increases in auroral activity [16,19]. This record is summarised in Figure 3, along with a timeline of related scientific and societal events.

Figure 3: Distribution of pandemic influenza outbreaks reported from 1510 to 2020. (adapted from data given in Figure 2 in Morens, D.M. and Taubenberger, J.K., 2010, Influenza and other Respir Viruses, 4 (6), pp.327-337)