Author(s): Aman Gudeto

The study was conducted in the East Shoa and West Arsi Zones of Oromia Region with the objective to assess the functional traits of Arsi cattle in their native areas. Two hundred forty cattle keepers were identified using random sampling techniques. The study was conducted in five districts, namely Adami Tullu Jidokombolcha (ATJK), Bora, Dodola, Shala and Negele-Arsi. The survey revealed that the age at first mating, age at first calving, and calving interval of Arsi cattle at on-farm level were 43.5, 55.9 and 19.1 months, respectively. The lactation length and milk yield of Arsi cattle were 9.6 months and 1.66 liters per day, respectively. The working life of oxen was 7.7 years. The observed results on reproduction and production of Arsi cattle at on-farm level are good indicators of information for further evaluation of their performances.

Ethiopia is believed to have the largest livestock population in Africa. Ethiopia’s Ethiopian cattle population is above 70 million heads [1]. Most cattle reared in the country are indigenous (97.76%) and minuscule numbers are hybrids and exotics [1]. Indigenous cattle provide relevant and sustainable production due to better adaptive ability and reproduce in the harsh environment. Local cattle have desirable traits, which are preferred by the farmers and give subsistence milk production within existing environmental stress [2].

Cattle are the most important livestock species and are reared in all agro-ecologies and provide various options for smallholders and pastoral communities [3]. They provide milk, meat and other social functions to agrarian communities. However, the productivity of cattle is limited by several constraints that include the high prevalence of diseases and limited feed availability [4]. Their productivity is low due to low-level input, traditional husbandry practice, fewer genetic improvement interventions and environmental stress [5].

There is growing milk demand in the country in parallel to population and urban growth. To increase the milk supply in the country, it is very imperative to improve the genetic makeup of the local cattle through proper breeding and management [6]. Moreover, it is skeptical to plan and design a production improvement strategy without considering the production and reproduction potential of the cattle.

The Arsi cattle are well adapted to the harsh environment and distributed through different agro-ecologies [7]. The breed is mainly kept for draft power and milk production purposes by agrarian communities. The performance information for indigenous cattle mainly comes from the on-station farms. The on-farm information on functional traits of Arsi cattle is little. Hence, the study was designed with the objective of assessing the functional traits of Arsi cattle in their breeding tract.

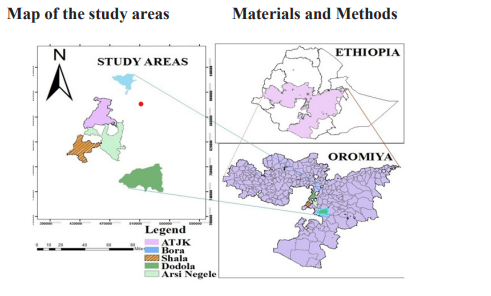

Map of the study areas Materials and Methods

Sample and sampling design A multi-stage sampling technique was employed for the selection of study districts and respondents for interview. Accordingly, ATJK and Bora from East Shoa Zone and Dodola, Shala and NegeleArsi districts from West Arsi Zone were purposively selected based on cattle population and accessibility. The samples were proportionate according to the total numbers of farmers per district. Accordingly, a total of 240 households were randomly selected and interviewed. Two Kebele were selected from each district based on cattle potential, and farmers who have cattle were listed and randomly selected for interviews.

The survey was conducted through field observation and direct interviews. The semi-structured questionnaire was developed and tested before administration. Some re-arrangements, reframing, and corrections were made after the questionnaire test. The questionnaire included respondent education levels, main income sources, herd structure and functional traits like on-farm reproduction, production and draft power. Every respondent was informed about the objective of the study while conducting the survey. Focus group and key informant discussions were conducted to strengthen the data from the semi-structured questionnaire.

Questionnaire data gathered during the study period was checked for any error, coded and entered into excel spread sheet. The SPSS statistical software (Ver. 24) was used to analyses data. Descriptive statistics like percentage and mean were used to present the analyzed data, while chi-square was used to compare the variation of education level. In all the cases, 95% confidence level and 0.05 absolute perception errors were considered.

The findings indicate that the male-headed households were more than those of the female-headed households (Table 1). The result further indicated that most of the respondents (irrespective of the locations) were from the agrarian community and depended on agronomic and livestock husbandry practices for their livelihood.

Table 1: Sex and major income sources of respondents (%)| District | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Description | ATJK | Bora | Dodola | Shala | Negele-Arsi | Overall |

| Sex | Male | 78 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 79 | 75.4 |

| Female | 22 | 29 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 24.6 | |

| Income | Crop | 97 | 99 | 99.2 | 93.8 | 95 | 96.8 |

| Livestock | 94 | 94 | 92 | 95 | 93 | 92.8 | |

| Business | 2 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 1.82 | |

Notice: Respondents asked income sources in the form of binary questions

The results as presented in Table 1 indicated that most of the respondents were males, which may be ascribed to societal norms as most of the families in the country are headed by males [8]. The male members usually do not appreciate female members of the family communicating with strangers, which too is in close accordance with the findings of Kebede et al. from southern Ethiopia. This, of course, is not appreciable as many husbandry practices are female specific and information regarding the same may not be provided correctly by the male respondents [9].

The study further indicates that most of the respondents belong to the agrarian community and earn their livelihood from crop and livestock husbandry practices, which too is in close accordance with the reports of Tariku from the southern part of Ethiopia [10]. The importance of livestock and crop husbandry in the region too is in close accordance with the findings of Emana et al. from the western part of the country. The interdependency of crop and livestock production serves as a synchrony between the efficient utilization of crop residues and manure. The synergistic approach of rearing livestock and crop cultivation ensures that producers have access to cash which they can obtain by selling off some animals in case of emergency [11].

The education levels of the respondents are presented in Table 2. The respondent education levels were not varied across the district. The finding indicated that most of the respondents, irrespective of the locations, were educated between class 1 and 8, followed by those who were not educated at all.

Table 2: Education level of respondents (%)| District | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | ATJK | Bora | Dodola | Shala | Negele-Arsi | Overall | χ2 |

| Illiterate | 30 | 23.7 | 26.9 | 25 | 28.6 | 27.1 | 0.72 |

| Read and write | 14 | 21.1 | 11.5 | 13.6 | 10.7 | 13.8 | |

| 1-8 grade | 48 | 50 | 46.2 | 52.3 | 41.1 | 47.1 | |

| 9-12 grade | 8 | 5.3 | 15.4 | 9.1 | 19.6 | 12.1 | |

The results indicated that most of the respondents were educated till elementary school, followed by those who were illiterate. The observations are in close accordance with those of Tariku [10] from Hadiya Zone. Literacy/education of the respondents can play an important role in cattle husbandry practices, especially if recording of products and husbandry practices needs to be carried out. Literacy enables the respondents to appreciate techniques for the management of livestock, including adoption of improved technologies [12].

The results presented in Table 3 show that the herd structure of the steers/bulls (bull calves, castrates and the bulls) did not vary across the study areas. However, the numbers of steers/bulls were fewer at Bora and higher at Shala.

Table 3: Herd structure| Structure | District | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ATJK | Bora | Dodola | Shala | Negele-Arsi | Overall | |

| Male (<3yrs) | 32.4 | 2.3±1.4 | 1.3±1.1 | 2.5±1.7 | 2.8±1.8 | 1.9±1.5 | 2.2±1.6 |

| Bulls | 21.3 | 1.6±1.5 | 1.1±2.7 | 1.4±2.1 | 1.7±2.0 | 1.3±1.6 | 1.4±2.0 |

| Castrated | 46.3 | 3.5±2 | 2.8±2.4 | 3.1±2.2 | 3.4±2.5 | 2.7±2.1 | 3.1±2.2 |

| Total | 100 | 7.3±3.9ab | 5.6±5.3b | 7.1±5.2ab | 7.9±4.9a | 5.8±4.3ab | 6.7±4.8 |

| Calves(<1yrs) | 20.5 | 2.1±1.7 | 1.3±1.2 | 1.9±1.5 | 2.3±1.7 | 1.7±1.3 | 1.9±1.5 |

| Heifers | 26.7 | 2.6±1.6 | 2.1±2.9 | 2.6±1.8 | 2.6±2.1 | 2.3±1.7 | 2.5±2.0 |

| Cows | 52.7 | 5.1±2.5a | 3.7±3.5b | 4.9±3.6a | 5.6±4.1a | 4.5±2.8ab | 4.9±3.4 |

| Total | 100 | 9.8±4.6a | 7.1±7.0b | 9.8±6.2a | 10.5±6.7a | 8.5±4.8ab | 9.2±5.9 |

Male total, total female and cows were significant difference at (P<0.05) across the rows

The total number of male and female cattle was higher in Shala district, which may be ascribed to the fact that the higher number of

cattle raised at Shala per household may be due to the fact that the community relies more on livestock income sources. Shala has low

land size and overcomes the feed shortage by moving cattle to areas where common grazing land is available, like Abjeta and Shala

lake territory, and rift valley areas that are not suitable for cultivation. The steer number is higher in the herd because farmers keep

more drafts, which is in accordance with the findings of Mokonnen et al. [13]. The result indicated that overall male and female per

district varies, which is in accordance with the report of Andualem et al. from the southern part of the country [14]. The proportion

of females is higher than males in the cattle herd size, which is in accordance with the report of Gebretnsae et al. from the northern

part of the country. The proportion difference in the herd structure might reflect the management decisions of the cattle keepers,

which are guided by the production objectives [15].

The results pertaining to the reproductive traits of the Arsi cattle reared in the study areas are presented in Table 4. The findings indicate that traits such as age at first mating of heifers, age at first calving and calving interval did vary across the studied locations.

Table 4: Reproductive indicative information| District | AFM(Month) | AFC(Month) | CI(month) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATJK | 43.6±8.1ab | 56.1±8b | 19.2±6.2b |

| Bora | 43.5±6.5 ab | 57.2±6.8bc | 20.3±6a |

| Dodola | 41.7±8b | 53.6±8c | 17.3±5.5c |

| Shala | 43.6±8.1a | 55.3±7ab | 18.7±6.3ab |

| Negele-Arsi | 44.9±9.6a | 57.6±10.5a | 20.1±6.1a |

| Overall | 43.5±8.1 | 55.9±8.2 | 19.1±6.1 |

AFM: Age first mating, AFC: age first calving, CI: calving interval

The age at first service is the age at which a heifer reaches sexual maturity to accept service for the first time. Age at first calving is

the age when a pregnant heifer gives birth for the first time in her life. The calving interval is the time length between two successive

calf births [16]. The findings from Table 4 pertaining to the reproductive performances of Arsi heifers/cows indicate that there are

differences in age at first mating, age at first calving and calving interval, while the values were lower at Dodola and higher at NegeleArsi district. The age at first mating, age at first calving, and calving interval of cattle are mainly influenced by the management they

receive and genetics [4]. The age at first mating, as observed in the study, is in close accordance with those of Tewelde et al [12]. for

Begait cattle, but higher than the age at first mating reported by Assemu et al. for Fogera cattle [17]. The age at first mating trait has

an economic impact; heifers with delayed age at first mating alongside the age at first calving have fewer calves, which influence the

overall life productivity. The observed calving interval in the study was in close accordance with those of Kereyu cattle from the

Fantale district of Oromia [2]. Zebu cattle have a longer calving interval when compared to the taurine breeds. But, calving intervals

have low heritability and this can be enhanced through proper feeding and management [5].

The results pertaining to the production traits of Arsi cows are presented in Table 5. The lactation length did not vary across the studied areas, but there were differences in the daily milk yield of the cows.

Table 5: Production performance indicative in studied areas| Variable | District | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATJK | Bora | Dodola | Shala | Negele-Arsi | Overall | |

| LL (month) | 9.6±2.1 | 9.7±2.3 | 9.2±2.7 | 9.3±2.3 | 10.0±3.2 | 9.6±2.6 |

| DMY (lit) | 1.67±0.3ab | 1.47±0.4a | 1.82±0.2b | 1.56±0.4a | 1.71±0.3ab | 1.66±0.4 |

| AFBD(month) | 43.5±10.5b | 48.1±8a | 48.4±8.2a | 46±7.7ab | 44.7±9.1ab | 46±9 |

| OWLT (yr.) | 7.7±1.5ab | 8.4±2.3a | 8.4±2.4a | 7.6±1.6ab | 7.3±1.6b | 7.7±1.5 |

LL: lactation length, DMY: Daily milk yield, AFBD: Age at first

which the bulls are serve for draft purpose, OWLT: Ox working

life time

The observed values of lactation length are in close accordance

with the findings of Bayou et al. for the Sheko breed of cattle from

southern Ethiopia [18]. However, the results are lower than those

reported by Damite for the Fogera breed, while the reverse is true

for cattle reared in the Sidama Zone of southern Ethiopia [19,20].

The observed values of lactation length are below the standard.

Lactation length is one of the important factors which decide the

profitability of keeping a particular cow. Cows with fewer days in

lactation are usually unprofitable for the dairy farmers, which has

an adverse economic impact on the owners. However, cows with

very long lactation length usually have a long calving interval,

which is also not favorable as such cows often have fewer lifetime

calving [21,22].

The results indicate that daily milk yield is higher in cows reared

at Dodola, which might be ascribed to the better management of

the cows in the area [2]. The daily milk yield of the current study

is similar to that reported by Agere et al. for Horro cattle [23].

However, the result is lower than the daily milk yield of Begait

cattle, which was reported by Tewelde et al. from the northern

part of the country [12]. The difference observed in milk yield

can be attributed to the genetic makeup of the cows, parity, stage,

availability of the nutrients and management provided by the

cattle owners.

The study also indicates that the age at which the bullocks are

put to work is earlier at ATJK, while the reverse is true for the

bulls raised at Dodola. This may be ascribed to the importance

of agrarian activities in the region. However, the age at which

the bulls are ready for work is late when compared to the other

breeds of bulls/oxen like the Horro cattle breed [24]. The average

lifetime work of the Arsi oxen varied across the studied locations,

and this may be ascribed to the availability of young in the herd

for replacement and the management received by the bulls during

their lifetime [24]. It has been noticed that the plough and the

associated harness can help in improving the draftability and

ploughing capacity, thereby making it more comfortable for both

the owner and the bullocks alike [25].

The variation in milk production among the sampled populations is a promising opportunity for designing breed improvement through selection to maintain this valuable genetic resource and improve its contribution to the livelihoods of its keepers. However, the observed result is indicative of the performance of Arsi cattle at onfarm level. Furthermore, it needs detailed performance evaluation to get the actual information and to set a proper breeding strategy.