Author(s): Youssef Courbage

This text risks quickly becoming obsolete because of the unforeseeable upheavals of recent months. The coronavirus pandemic which is raging throughout the world has not spared the Arab world, even if its epidemiological severity: incidence of infection, mortality, etc. is far from reaching the heights it has achieved elsewhere, particularly in America and Europe. In addition, the Arab countries are very diverse, not suffering evil with the same intensity; some are more spared than others for reasons which are only partially understood.France

But if the prevalence of the pandemic and mortality there have been relatively moderate, their economic, social and political consequences will be devastating. Undoubtedly more in these latitudes than in developed countries. It would therefore be appropriate, once we have sufficient hindsight, to study the effects of demography on Arab societies in three stages rather than two: that of the demographic transition, then that of the counter transition and finally that of the return to the transition, but this time pulled by poverty (poverty led transition).

Demography makes it possible to judge on pieces, far from received ideas. This discipline, which may seem arid with its numbers and curves, however, allows us to go to the depths of the intimacy of human behavior, to measure as objectively as possible the behavior of human beings from birth to death, to see if there are fundamental differences between groups and to realize the divergences or convergences between them.

Fertility (or birth-rate) would be the demographic criterion that would best show the differences between groups, especially between Muslims and Christians, Arabs and Westerners. The world map shows enormous variations: if in Sahelian Africa a woman always has an average of nearly 7 children during her fertile life, in the Far East she is satisfied with 0.9 children or even less as in Taiwan and South Korea [5]. A simplistic view would automatically place Muslims and Arabs at the higher end of the fertility range. However, if the Muslims of Niger have 7 children per woman on average, those of Iran - yet Islamic Republic - are content with 1.7, fewer than in most European countries [6]. In Arab countries, fertility, far from being homogeneous, varies greatly from one country to another. Therefore, we should review the Manichean ideas and realize that there is hardly an insurmountable gap between civilizations, Muslim and Christian in particular.The demographic transition is an established reality in the Arab world. Since the 1970s, fertility has declined significantly. A demographic revolution, which stems from other revolutions: cultural, mental, health, etc. that the world has known, in Europe first, since Martin Luther in the 16th century, and which spread around the world to reach the Arab world from Morocco to Oman, half a century ago.

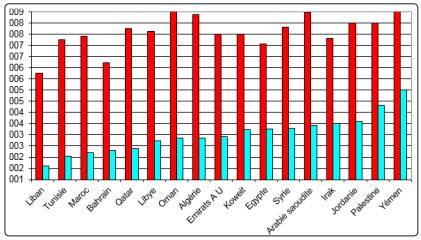

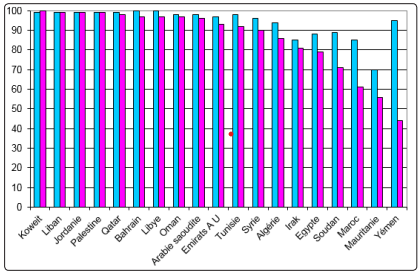

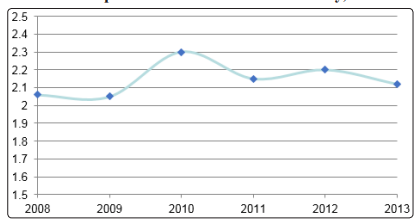

The strength of this demographic and fertility transition is patent (Chart 1).

Source: Censuses or Surveys National Data, or otherwise United Nations Population Division and US Census Bureau.

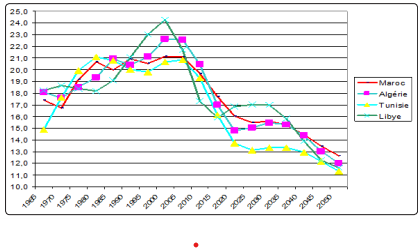

Admittedly a late transition, but dazzling judging by the Total fertility rates (or the average number of children per woman) before the transition (the sixties of the last century) and by 2010, just before the Arab springs. The implications, political in particular, of this change of course are manifold. Political scientists, in the movement of Huntington, explained the political violence, that of the Arab world by the youth of the population, the ?youth bulge? or the demographic pressure exerted by the young people. When the proportion of young people at the ?turbulent? ages say 15 to 24 years increases in the age pyramid, political violence tends to increase.Chart 2: The youth bulge (proportion of the age group 15 to 24 years to the total population) in the Maghreb and Mashrek from 1965 à 2050

Source: Same as Chart 1.

Chart 2 illustrates this phenomenon in the Maghreb and the Mashreq with the proportion of young people increasing in some cases from 15-18% in 1965 to 22-24% in 2005. But the explanation of political violence by demographic growth falls short if we look at the other part of the curve, where we can see the collapse of this demographic bulge of young people between 2005 and 2050. A disappearance of political violence?

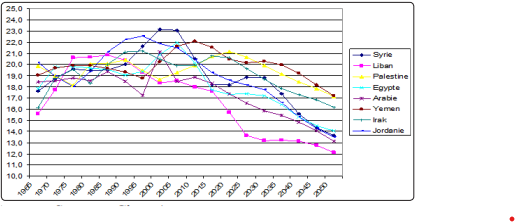

One could therefore bet on a substantial improvement in living conditions in the wake of this new demography that was looming on the horizon. Unsustainable natural rates of increase over 3% per year have been followed by more moderate rates. We spoke of the ?demographic window of opportunity? or with a bit of exaggeration, ?the demographic miracle?, more modestly ?the demographic dividends?. Indeed, the demographic deceleration was contributing to the increase in national savings, investments - and among these so-called ?economic? investments compared to ?demographic? investments. Hence an increase in the Gross Domestic Product and employment opportunities. With less pressure from young people seeking employment, it was realistic to envision a decrease in social unrest and political violence. Chart 3 shows in the case of Morocco how gross entries and net entries in the labor market changed and will change between 2005 and 2030, an example that can be transposed to other Arab countries.Chart 3: Gross and net entries (thousands) in the labor market, Morocco, 2005-2030

Source: Haut-Commissariat au Plan du Royaume du Maroc, Censuses of 2004 et 2014 and Enquêtes nationales sur l?emploi, Rabat, Various Years.

With less pressure to enter the labor market, the place of women in working life could only improve, competition being less fierce, women, most often relegated to domestic tasks and the maintenance of children, could more easily find a place outside the marital home, except when the well-anchored cultural motives opposed it.The emerging demographics, was also a chance offered to the Arab countries to catch up with their backwardness in education and try to reach the records of some formerly underdeveloped countries where the attendance rate at university level is now around 75%! However, Arab countries have long suffered from an incredible growth in school-age children; 4% per year as in Algeria, a financial pit where education took 10% of GDP and a third of the state budget.

The demographic transition has also contributed to the reduction of inequalities in countries where it was reaching its peak. This may seem surprising. Yet before the transition, say before the 1970s of the last century, the poor sections of society received, it is well known, the minimal part of the National Income. Moreover, to worsen the inequalities, they had to distribute this small part of this National Income among a large number of people. Indeed, the number of children per household was much higher in the poor categories than in the well-off ones; the middle categories being in an intermediate position. The demographic transition, by spreading to the whole of society, has made it possible to level fertility, with the result of reducing the glaring gaps between the average number of children of different social categories. Inequalities are still rife in all the countries of the region, but they would have been even more acute if the demographic transition had not happened through this.The Arab world, belatedly, was reliving this universal process of increasing the level of education of the population. By generalizing access to reading the Bible to the entire population, Martin Luther during the 16th century, was, undoubtedly, at the origin of these upheavals, one of the least expected effects of which is the secularization of minds and the generalization of birth control and contraception. The rise in the level of education also carried with it revolutionary ferment, as in the England of Cromwell in the 17th century and the France of Robespierre in the 18th century. Today, the Arab Spring of 2011 and the Hiraq of 2019 remind us of the universality of these processes.

Chart 4: Proportion (%) of the youth (15 to 24 years) by sex (men in blue, women in red) which were able to read and write at the start of the Arab springs

Source: National Data and Unesco Institute of Statistics, Literacy Statistics MetaData Information Table, 2015.

Access to primary school, this more than banal phenomenon, is what precipitated the process of change. In this regard, the Arab world is now in a good position. Young people aged 15 to 24 are literate practically everywhere and regardless of their gender. Graph 4 shows this clearly, but shows some laggards, with by level of severity Yemen, Mauritania, Morocco and Sudan.Education induces a spirit, say ?secular?. Procreation becomes a voluntary act, the decision of which is up to the couple alone, without it being dictated by the Power, the tribe, the ?ancestor? (or ... the mother-in-law).

The demographic transition involves the collapse of mortality, without which fertility could not have fallen on a lasting basis. As a result, life expectancy in the Arab world has almost doubled since the fifties of the last century, now approaching 80 years for women in some countries. The decline in mortality has certainly contributed to the decline of fatalism, traditionally very widespread in the Arab world. Before the progress of medicine in particular, the Arab individual was the instrument of qadar (destiny). Everything was maktoub (written, pre-determined): disease, pandemics, accidents, death, finally. With a now high life expectancy, today one can feel ?immortal?, even if it is an illusion, but which has the advantage of boosting the morale of the individual.Traditional hierarchies have entered into crisis. In the patriarchal society that prevailed until then, not long ago, the father dominated, terrorized his children, especially his daughters. Source of unease, the father was often illiterate or poorly educated in the face of increasingly educated children. The husband dictated his will to his wife, who was mostly illiterate or poorly educated. The sister owed obedience to her brother.

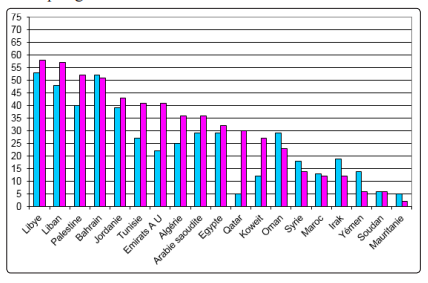

Chart 5: Access (%) to University Education by sex (males in blue, Females in red) in the Arab countries at the Eve of the Arab Springs

Source: See Table 4.

As it spread, the education sparked a series of questions within the family. But the family is only the ?micro? scale whose metamorphosis reverberates and amplifies at the ?macro? scale, society. Mezzo voce developments could hardly fail to resonate in society. The individual who questions the authority of the father will soon question that of the ?father? of the nation (a monarch or a president, most often for life).The demographic transition with all its components and its ins and outs is not ?a long quiet river?. In the case of Arab countries, certainly. Contraception, now almost generalized, in its modern or traditional forms, is largely beneficial because it allows the couple to choose the number of their children according to their material possibilities. But contraception, by allowing the release of the wife?s body, allows her to escape the grasp of the husband, which is not without raising concerns, which sometimes went beyond the husband himself and spread to her family.

Little is mentioned about the possible relationship between a demographic transition which presupposes a certain dose of empowerment, even liberation of women, particularly in terms of sexuality and the social and political unrest that could result from it. In the Arab world, there has been a certain form of radicalization, especially among young people, which is not unrelated to the demographic transition and its presuppositions, the rise of forced celibacy in particular. It generated a certain dose of sexual frustration which could at best be invested in a form of return to the past, Salafism or at worst unfortunately in political radicalization. A phenomenon that is not strictly Arab or Islamic as shown in the case of Ireland where the radical movements (Sinn Fein and IRA) had fed on the frustration of young men.But these backward-looking attitudes and behaviors should not be overstated. The new family model, with the father, the mother and a smaller and smaller number of children, that of the nuclear family, was widely accepted. We can go further and say that the large and hierarchical family of the past corresponded to an authoritarian political regime. As a result, the transition to a restricted family appears to be a necessary condition, even if it is not sufficient for exiting authoritarianism.

These words - optimistic - in the craze aroused by the Arab Spring could seem naive, judging by the political setbacks that followed everywhere after the Arab Spring, where we saw the Islamist or authoritarian parties take the lead. power for good or temporarily as in Tunisia or Egypt or see them sink into civil war as in Syria or Yemen. It is not easy to explain these refluxes, but it is certain that societal progress has not found favorable echoes in the political body, where opposition to the regimes in place was most often shattered into a dust of groupuscules. It should also be noted that the Arabs have only known secular or ?secular? parties in their most repulsive aspects: despotism, repression or corruption.The countries undergoing a demographic ?counter-transition?, a rise in their fertility index after a significant decrease, are spread all over the Arab world. They should therefore be individualized given the great heterogeneity of the contexts.

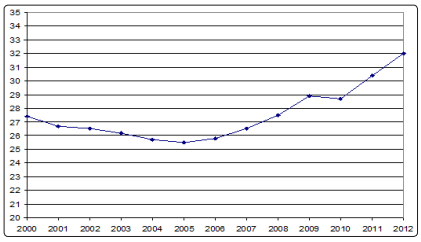

Let?s start with Egypt, Umm el Dounia (the mother of the world) for the Arabs, the most populous and long the most influential of the Arab countries. With more than 102 million inhabitants, residents and a dozen others spread around the world, Egypt is one of the countries with the highest density in the world taking into account only non-desert surfaces: nearly 2,600 inhabitants per km2 .Chart 6: The decline, then the rise of the crude birth rate in Egypt until the Arab springs, 2000-2012

Source: CAPMAS, Egypt Statistics, Demographic Birth Rate (2019), at: https://bit.ly/2S1JAsm

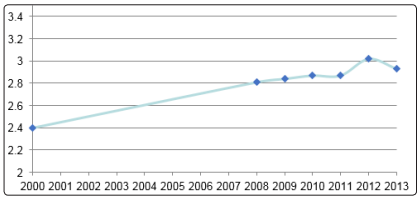

For a century or more, imbued with modernism, the country?s authorities (political or even religious) have been concerned about uncontrolled demographic growth, aware of the urgent need to reduce fertility there. Without much success. Both under the Khedives and up to King Farouk. Only Gamal Abdel Nasser with his charisma (not devoid of humor…) had succeeded in initiating a family planning program and convincing the Egyptians to have fewer children. But since his untimely death in 1970, the results in this area have been most tenuous. The increases in birth rates and the fertility rate show this. The Egyptian spring in particular paradoxically slowed down the decline in fertility. Thus in 2015, the fertility rate exceeded 3.6 children per woman (according to the US Census Bureau, slightly less according to the United Nations Population Division). It is enormous. Considering the material possibilities of the country and in comparison with Morocco, 60% more or twice more than in Lebanon. Algeria, the second largest Arab country in terms of population, fertility is steadily increasing, Arab Spring or not. From 2.38 at the end of the civil war in 2000-2005 to 3.05 in 2015-2020.Chart 7: The unabated increase of the Total Fertility Rate in Algeria (2000-2013)

Source: Office National de Statistique, Evolution des principaux indicateurs (2019), at: https://bit.ly/3n1u4LA

As for Tunisia, which has been since Bourguiba, the ?beautiful model?, the champion of the demographic transition of the region and the precursor of the Arab Spring, fertility started from a ?European? level in 2005: 2.02 children, to 2.27 in 2010 and 2.47 in 2014, which prompted a journalist from Tunis to say ?help, the fertility rate is back on the rise! And appalled the country?s demographers and other social scientists, as if the resumption of fertility was bad omen for the Tunisian spring. However, since 2014, the movement is once again on the decline. But with 2.17 children per woman in 2018, fertility is higher than it was 10 years before.

Source: Institut National de la Statistique, Indice synthétique de fécondité (2019), at: https://bit.ly/3jb3Q6G

Morocco remains the only country in the North African zone to have continued its demographic transition, with a fertility rate of 2.21 children per woman in 2014. But this result is not unanimously taken for granted in view of a recent survey. which places it significantly higher at 2.38 in 2018. This does not gowithout causing some concern in this country where we are very aware of the close links between fertility and modernity.

It would be tedious to review all the Arab countries to gauge the reality of their demographic transition in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. At first glance, it appears that 10 of them have continued their transition, 6 have undergone a reversal or an end to the transition, 2 are experiencing more complex situations with ups and downs, 1 country (Libya) is in total blur. Therefore, a majority of Arab countries would still be in the process of modernization, as evidenced by the demographic transition. Paradoxically, it is often the countries apparently the least disposed to demographic modernity, where the transition is maintained, such as Saudi Arabia or the small Gulf emirates: United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Bahrain (and Lebanon, an exception). The fertility of nationals and foreigners continued to decline despite their unparalleled wealth, their policies in favor of large (national) families, their desire to replace the many foreign populations with nationals.Syria, before the Arab Spring, had maintained very high fertility, especially for its large majority Sunni, while religious minorities continued to reap the fruits of the transition. Yemen, Iraq (except autonomous Kurdistan) still had high fertility, more than 4 in the first 2 countries in 2015, more than 3 in Syria, despite rampant pauperization; wars then seemed to stimulate fertility rather than reduce it.

Until very recently, Jordan and Palestine, for often political reasons linked to the heterogeneity of their populations and to the rivalries that it induces, maintained fertility rates significantly higher than those which would have resulted from their levels of relatively high education. In Jordan, there are Jordanians ?of stock? and Palestinians mainly resulting from the exoduses of the wars of 1948 and 1967. In the State of Palestine, the Palestinians, cohabit - rather badly - with Israeli colonists who number more than 800,000 settled by force in the West Bank and annexed East Jerusalem. Their fertility exceeds that of sub-Saharan Africa, and that of the Jewish population of Israel is increasing with metronome regularity, allowing it to soon equal if not exceed Palestinian fertility, in Israel which is already done and in the West Bank. in a few years.But, if rather than countries, we took their populations into consideration, the situation would appear quite different, because the ?broken down? countries of transition such as Egypt, Algeria, Iraq, Syria etc. weigh heavily in the balance because of their demographic size: to equate enormous Egypt with tiny Bahrain would be misleading. There, it would be rather a minority of the Arab populations, of the order of 40%, who would continue to benefit from the demographic transition.

This new observation on Arab demographic transitions may seem severe and suggest a step backwards on modernization, with a withdrawal towards the traditional family, rigid social structures and ultimately authoritarian regimes. But the insistence on fertility as the privileged criterion of modernization, risks making us forget the importance of other criteria which have continued to advance, such as mortality, that of children, women of childbearing age, adults and children. seniors; with an unabated rise in life expectancy. We must also consider the metamorphoses of marriage, its average age, its consanguinity, divorce and repudiation, all criteria whose evolution reflects a certain form of modernization. We should therefore be aware of the ?ratchet effect? dear to economists, which postulates that a phenomenon such as the democratic transition can continue even if one of the initial causes the demographic transition has broken down (temporarily).While there has been a reversal of trends, or even a demographic counter-transition, the reasons are complex. The ?return of Islam? has been mentioned as one of the reasons for the rise in fertility. It is true that in Morocco, for example, an Islamist prime minister had advocated the necessary return of the housewife, or close to the Arab world, in Turkey, an Erdogan who implored the Turkish woman to have at least 4 children. To come back to Egypt, an officially anti-natalist country but where fertility has risen sharply, one is struck by the fact that popular culture, on the other hand, is pro-natalist and that the desire of many children is there.

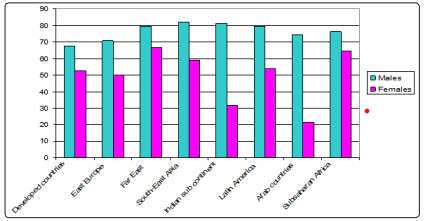

But without completely dismissing explanations relating to the mentality or the collective unconscious, one must also take into account the material realities which can bend the fertility curve in one direction or the other. In Egypt, but in other Arab countries as well. The labor market which had opened up to women, increasingly educated and eager to leave the family fold, tended to close more and more. For the most educated Egyptian women, those who attended university, the employment rate literally collapsed from 56% in 1998 to 41% in 2012. For those who only attended secondary school, the results are not more satisfactory, with a decrease from 22% to 17%. For the illiterate and for those who had only primary school to their credit - a small part of the affected population - activity rates remained at a very low level. The translation in terms of fertility is immediate: a return to the home, the abandonment of professional life favors the resumption of fertility, female activity being with education, perhaps even more so, the most important agent of efficient birth control.This demographic, even civilizational rift concerns the entire Arab world. Let the job market slip more and more under the feet of women. The following chart shows that on a planetary scale, the Arab world is far behind other regions of the world.

Chart 9: Employment rates by sex in the different regions of the world around 2013

Source: ILO, The gender gap in employment, what?s holding women back? (December 2017), accessed on 28/9/2020, at: https://bit.ly/3371HDt

While the employment rates for men are more or less the same, with little variation, the employment rate for Arab women has plunged very low to just around 20%. For example, it is around 70% in the Far East and over 60% in sub-Saharan Africa. Even the Indian subcontinent: 30% is better off. It must be made clear that this is an Arab problem, not a Muslim one. The huge Indonesia of 275 million inhabitants, 90% Muslim, has femalelabor force participation rates of 51%, 2.5 times higher than those of Arab countries and largely explains its demographic transition and its enviable economic performance.At the end of this demographic journey and its socio-economic and political correlates of the post Arab Spring, the findings can only be mixed. The stagnation of the demographic transition, or even the counter-transition, would not bode well. We can even mention the winter that would have followed the Arab Spring, a harbinger of its twilight?

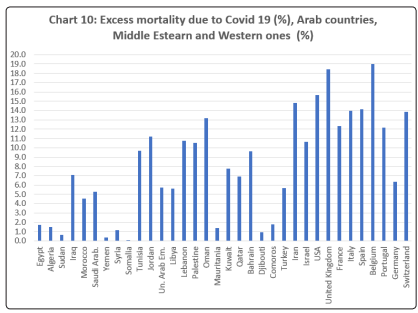

Besides, age-structure should be taken into account. Because of high fertility in most Arab countries, the share of the elderly, those more exposed to deaths and to Covid deaths are lower than elsewhere. Hence, in terms of international comparisons, this age factor should be considered. Sex distribution may also have an impact, since males are more exposed to death. Therefore those Arab countries with a higher propensity for international migration would be less exposed to mortality, since males emigrate usually more than females.

| Cumulative | Covid death | Normal CDR | Total CDR | Excess mort | % Covid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Covid deaths | rate (p.1000) | (p.1000) | (p.1000) | Covid (%) | deaths |

| Egypt | 9512 | 0,1 | 5,7 | 5,8 | 1,7 | 1,7 |

| Algeria | 2904 | 0,1 | 4,7 | 4,8 | 1,5 | 1,4 |

| Sudan | 1831 | 0,0 | 7,1 | 7,1 | 0,6 | 0,6 |

| Iraq | 13091 | 0,3 | 4,8 | 5,1 | 7,1 | 6,6 |

| Morocco | 8352 | 0,2 | 5,1 | 5,3 | 4,5 | 4,4 |

| Saudi Arab. | 6389 | 0,2 | 3,6 | 3,8 | 5,3 | 5,0 |

| Yemen | 615 | 0,0 | 5,9 | 5,9 | 0,4 | 0,4 |

| Syria | 938 | 0,1 | 4,8 | 4,9 | 1,2 | 1,2 |

| Somalia | 132 | 0,0 | 10,5 | 10,5 | 0,1 | 0,1 |

| Tunisia | 7048 | 0,6 | 6,3 | 6,9 | 9,7 | 8,8 |

| Jordan | 4354 | 0,4 | 3,9 | 4,3 | 11,2 | 10,1 |

| U. Ar. Em. | 888 | 0,1 | 1,6 | 1,7 | 5,8 | 5,4 |

| Libya | 1919 | 0,3 | 5,1 | 5,4 | 5,6 | 5,3 |

| Lebanon | 3397 | 0,5 | 4,6 | 5,1 | 10,8 | 9,7 |

| Palestine | 1865 | 0,4 | 3,5 | 3,9 | 10,5 | 9,5 |

| Oman | 1532 | 0,3 | 2,4 | 2,7 | 13,2 | 11,7 |

| Mauritania | 425 | 0,1 | 7,1 | 7,2 | 1,4 | 1,3 |

| Kuwait | 962 | 0,2 | 3,0 | 3,2 | 7,8 | 7,2 |

| Qatar | 249 | 0,1 | 1,3 | 1,4 | 6,9 | 6,5 |

| Bahrain | 377 | 0,2 | 2,5 | 2,7 | 9,6 | 8,8 |

| Djibouti | 63 | 0,1 | 7,0 | 7,1 | 0,9 | 0,9 |

| Comoros | 105 | 0,1 | 7,1 | 7,2 | 1,8 | 1,7 |

| Total Arab | 66948 | 0,2 | 5,3 | 5,5 | 2,9 | 2,8 |

| Neighbouring countries | ||||||

| Turkey | 0,3 | 5,5 | 5,8 | 5,7 | 5,4 | |

| Iran | 0,7 | 4,8 | 5,5 | 14,8 | 12,9 | |

| Israel | 0,6 | 5,3 | 5,9 | 10,6 | 9,6 | |

| Western countries | ||||||

| USA | 1,4 | 8,9 | 10,3 | 15,7 | 13,5 | |

| United Kingdom | 1,7 | 9,4 | 11,1 | 18,4 | 15,6 | |

| France | 1,2 | 9,4 | 10,6 | 12,311,0 | ||

| Italy | 1,5 | 10,7 | 12,2 | 14,0 | 12,2 | |

| Spain | 1,3 | 9,2 | 10,5 | 14,1 | 12,4 | |

| Belgium | 1,9 | 9,8 | 11,7 | 19,0 | 16,0 | |

| Portugal | 1,3 | 10,8 | 12,1 | 12,1 | 10,8 | |

| Germany | 0,78 | 11,5 | 12,2 | 6,4 | 6,0 | |

| Switzerland | 1,1 | 8,1 | 9,2 | 13,9 | 12,2 | |

| Far East | ||||||

| South Korea | 0,0 | 6,4 | 6,4 | 0,4 | 0,4 | |

| Japan | 0,0 | 11 | 11,0 | 0,4 | 0,4 | |

| Singapour | 0,0 | 4,8 | 4,8 | 0,1 | 0,1 | |

| China | 0,0 | 7,5 | 7,5 | 0,0 | 0,0 |

Source: John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (5 February 2021) and United Nations, World Population Prospects, op. cit.

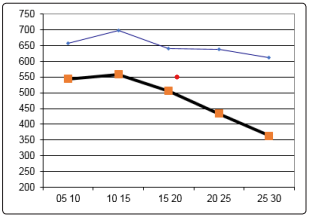

Judging by the better indicator of excess mortality due to the pandemics (mostly during 2020 until beginning February 2021), the heterogeneity of Arab countries affected by the pandemic is notable (Chart 10). The worst cases being Lebanon, Palestine (The West Bank, East-Jerusalem and Gaza strip), Jordan, Tunisia and curiously Oman [7]. North Africa and the Arab Middle East are less affected. In the non-Arab Middle East, the situation is sometimes better, in Turkey, and similar or worst in Iran and Israel). Excess mortality due to the pandemics in Western countries, is higher than in Arab countries but not to the extent that we could measure by more simplistic rates, such as death rate due to covid. This means that health situation in Arab counties is as worrisome as elsewhere.

Source: Table 1.

Yet it is not the sole concern. It would be presumptuous from these observations on the coronavirus pandemic, its incidence, the excess mortality induced by evil, to deduce its effect on marriage: celibacy of men and women, average age, divorce, repudiations and separations, especially fertility, this privileged demographic indicator of the destiny of societies.

For complex reasons, Arab countries include a small portion of the 2.4 million deaths that have so far occurred on the planet. Low satisfaction, because from Iraq to Morocco, the economic and social damage is already enormous and will undoubtedly increase. On this point there is unanimity in the scientific community. Gross Domestic Product, national savings, investments (especially so-called ?economic? investments, rather than ?demographic? ones) will fall sharply or many months to come, if not for years. Economic activity will shrink in all strata of society and unemployment will strike with an iron fist. Tourism, a major provider of jobs, will remain anemic for a long time. The many immigrant workers, in the Gulf countries or in Europe, will find it difficult to repatriate their savings which will have melted. These rich countries will become less and less providers of economic aid to Arab countries which need it badly.Thus, unfortunately, a third phase of the Arab demographic transition would begin, that of the transition driven by poverty. Fewer and fewer children because, young people will be less able to marry and will have to think much more sparingly when it comes to bringing children into the world.